We are now counting down the months to the end of the oil era – the age of convenient, cheap and abundant oil-fueled energy that has made the World we know today. This evolving energy crunch will shake the World to its foundations and bring almost unimaginable change over the next five years. Ajusting to a post-oil World presents governments with far and away their greatest policy challenge; the credit crunch is a mere blip in comparison.

In short, we are at (or as nearly at as makes no difference) ‘Peak Oil’ – the time when Earth’s ability to produce this finite resource peaks before starting its inevitable decline. Of course oil will still be produced in a hundred years’ time, but quantities will be tiny. What is different about this moment in history is that it is from now (or about now) that oil must start to reduce as a source of energy. There is simply no alternative.

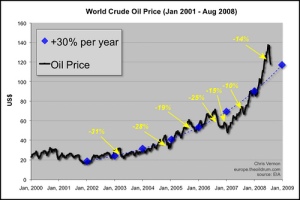

The market has been signalling the coming crunch through the price trend over the last few years as shown in figure 1 (from The Oil Drum blog) below (click for a better view).

The wiggly black line shows oil prices since January 2000, the blue diamonds show a trend line rising at 30% per year superimposed on to the oil price, and the yellow arrows shown the size of various temporary declines on the way. The fall of the last few weeks turns out to be actually rather modest compared with recent history. In fact, as the comments thread to the original article notes, a +30% trend, if sustained, means that the oil price doubles every 2.3 years and gets us to a price of $200 per barrel sometime in 2010. Scary!

I will return to the likely future price later, but first it is necessary to consider some of the supply and demand trends that will influence it.

Commodity market prices (including oil) are highly sensitive to small imbalances between supply and demand. When supply exceeds demand (as it did until recently) market forces bid the price down until marginal supply (in principle the most expensive to produce) get squeezed out because it isn’t profitable. Conversely, when demand exceeds supply then either supply must expand or marginal demand must be squeezed out. That, in a nutshell, is what started to happen in ernest a few months ago. Since supply didn’t increase much prices rose relentlessly until demand reduced. (Obviously this is a simplified account which ignores stock changes and complications arising from different grades of crude etc. but none of these change the big picture I am outlining here.)

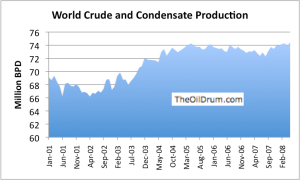

So the first question is, “Can producers increase oil supplies?” to which the answer is a depressing, “Not materially.” Figure 2 (also from the Oil Drum blog) shows gobal production for the last few years.

This shows an increase from roughly 2002 to 2004 (mainly due to Russian output recovering in the post-Soviet era) but since then it has been bumping along on a plateau despite the soaring prices which would surely bring any available new supplies to market. In fact, without the slight up-tick in supply in late 2007, one would probably conclude that the trend since 2005 was one of gentle decline.

The bumpy plateau is the result of the interplay of new supplies coming onstream and declining production from mature oil producing regions like the North Sea. Yet as figure 3 shows global oil discoveries peaked in the sixties.

As a general rule peak production in a newly discovered region occurs around 35 years after its discovery if there are no untoward technical or political impediments to production. In the real World such impediments often exist so the lag is slightly longer (think, for example, of the multiple problems of getting oil out of central Asia!).

That is basically why, as I reported in an earlier posting, there are relatively few of the megaprojects that can make a difference in the development pipeline. While the precise rate of decline from mature fields is difficult to forecast, the decline is inevitable and remorseless. In fact, production is already declining in most oil producing regions of the World. Oil is, after all, a finite resource.

Quoted reserves of any natural resource, including oil, always have an important caveat whether it’s explicitly stated or not – they are what it is judged feasible to produce based on existing technology and extraction economics. Thus, figure 3 above refers only to conventional crude. It does not include, (a) ‘unconventional crude’ (of which by far the most important are the Athabasca Tar Sands of Alberta), (b) the oil shales found at numerous locations around the World, (c) oil thought to exist under the ice of the high Arctic, or (d) in very deep water on continental margins. So the next question is, “Will changes to economics or technology make a difference?” and the answer is, “Yes, but not enough or soon enough to matter.”

The Athabasca Tar Sands are currently being developed at a hectic space but at a monstrous environmental cost and using huge quantities of natural gas. Thus, although the quantities in the ground are sometimes quoted as being comparable with all the oil in the middle east or similar, the amount that can ever be produced is far smaller. As a very rough approximation the Tar Sands should eventually produce enough for Canada’s own needs plus or minus a bit.

Oil shales are simply not economical with any known extraction technique and are unlikely to become so.

The cost of extracting conventional crudes from frontier areas (the high Arctic and deep sea) will, however, undoubtedly account for a growing share of World oil production in the years to come – but it’s growing from a low base as it is only recently that high prices have made it economical. Moreover, there is a great shortage of just about everything required – skilled people and drilling rigs in particular. Orderbooks for existing deep sea drillships are full for five years ahead and prices for new ones were raised by $100 million to $500 million per vessel (!) last year according to the NY Times so that even existing discoveries like those off Brazil cannot be properly developed for the moment.

Yet even if the Arctic and deep sea frontier areas could be exploited without delay they would not be enough to plug the growing gap from the decline of mature areas – we would have to discover the oil equivalent of a new Saudi Arabia every few years – and nobody thinks that likely.

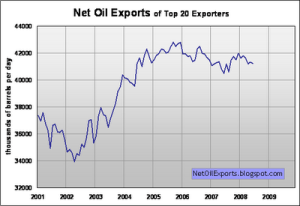

In yet a further complication, oil production is not the same as oil available for export. OPEC members are experiencing a massive economic boom on the back of high oil prices and booms mean more and bigger cars so their exportable surpluses are under pressure as shown by figure 4. Here the downward trend of the last three years is unmistakable even with the recent up-tick in production.

Moreover, two countries – the UK and Indonesia – have switched from being net exporters to net importers in the last few years. This trend will continue with the result that remaining exportable supplies become more and more concentrated – almost all in unstable parts of the World.

The net result is that we have between 18 months and 5 years before the remorseless decline of mature fields swamps all the other trends and the World’s oil production tips irrevocably into decline. It really isn’t possible to be more precise about timing because the statistics are dreadful and chaos theory rules. We should plan for the worst case but hope for a better one.

So what of future prices? There will be limited new supplies but it’s clear that massive new supplies will not, like the proverbial US Cavalry, come to the rescue in the nick of time. The main burden of adjustment will therefore have to come from the demand side and in the short term the twin pressures of economic recession and high prices at the pump (especially in the USA) are doing just that and causing prices to fall back.

In the slightly longer term – say two years – the only sensible strategy is to implement policies that reduce demand while developing substitutes for oil. If we succeed in limiting consumption oil prices might remain tolerable. If we don’t succeed in shrinking consumption, market forces will take over and enforce reductions through sky-high prices. I don’t imagine that the UK economy (or any other for that matter) could withstand $200 oil for very long without plunging into a severe recession that would be far more damaging than planned reductions.

In the coming weeks as time allows I hope to set out my view of how this could be done. Watch this space!